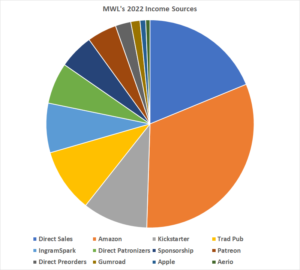

Here’s where my money came from in 2022. (For those seeing these for the first time, I did similar posts in 2019, 2020, and 2021.)

I’m a writer. My income comes from writing books and making them available. I publish both independently and through publishers. I don’t consult. I don’t seek out speaking fees. I desire to make my living as an author, creating and licensing intellectual property. I make my books available in every channel that offers reasonable terms.

How did 2022 look?

First off, my income is down about 20% since 2021. This is not a surprise. In 2020 and 2021, lots of folks stayed home and read. In 2022, pandemic or not, people sick of the isolation burst out into the world and read less. But the percentages might interest you.

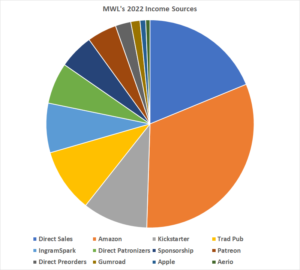

Here’s the detail.

Amazon – 31.35%

Direct Sales – 18.57%

Kickstarter – 10.01%

Trad Pub – 9.77%

IngramSpark – 7.60%

Direct Patronizers – 6.34%

Sponsorship – 5.33%

Patreon – 4.53%

Direct Preorders – 2.38%

Gumroad – 1.41%

Apple – 0.87%

Aerio – 0.66%

Kobo – 0.63%

Google – 0.36%

Draft2Digital – 0.11%

Barnes & Noble – 0.06%

Redbubble – 0.01%

Findaway – 0.01%

Here’s my rough conclusions.

First and foremost, I want to draw attention to income through my web site. Direct sales, 18.57%. Direct Patronizers, 6.34%. Sponsorships, 5.33%, and direct preorders, 2.38%. Taken all together, 32.62% of my income coming from sales through my web site.

Amazon provides 31.35%.

Amazon is no longer my biggest income source. I’m gonna say that again.

AMAZON IS NO LONGER MY BIGGEST INCOME SOURCE.

My biggest source of income is now my web site. People paying me directly. My goal of disintermediation works.

Yes, they’re only 1.27% apart. It’s a win by a nose. But I’ll take it.

This is personally important right now because I’m cutting Amazon off as a distributor of my new tech ebooks. OpenBSD Mastery: Filesystems will not be available on Amazon’s Kindle store. You can get Kindle copies everywhere but Amazon. Achieving this right now means it’s a fair comparison.

Mind you, it’s not entirely fair.

I have a Patreon, but I also host a Patreon-like program on my web site. To be a sincerely fair comparison, I would have to combine the Amazon and Patreon income. I haven’t done that math, because I have the answer I want. My web site brings in more than Amazon, I’m content.

For the record, I neither hate nor love Amazon. They are a retailer. They offer a variety of no-negotiation deals. I accept some. I reject others. I must not become dependent on, nor vulnerable to, any one business partner. Losing Amazon would hurt. I’d survive.

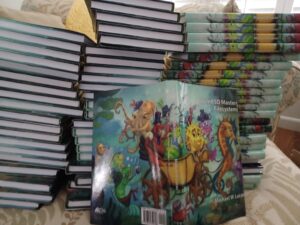

Kickstarter income for Prohibition Orcs is number three, but that’s deceptive. Kickstarters have fulfillment costs. I’ll post details on those once the campaign closes, but here’s a taste.

Between Kickstarter backers and Patronizers, that’s fifty Orcibuses I must mail. (Which reminds me, I must add the Orcibus to my web site. It’s a backer exclusive and not commercially available, but I should acknowledge it.) They cost over $600 to print, let alone mail. Most of these will get orc-leather covers.

So, yeah. Kickstarter is great, except for the ratio of income to expenses. The discoverability is delightful, though.

Traditional publishing income isn’t very large but to be fair, I haven’t published anything traditionally for a few years. I’m in discussions to do so, however.

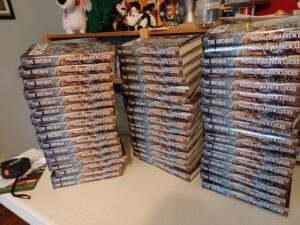

IngramSpark is “print paperback sales outside of Amazon, and all hardcovers.” Definitely worth doing. I use Amazon’s print program for paperbacks sold within Amazon.

After that, we have the smaller players. Gumroad, Apple, Kobo, Draft2Digital, and so on are ebook retailers. Are these tiny places worth selling through? Absolutely. Those nickels spend. If you bought the best ereader on the market and shop the Kobo store, I want you to buy my books.

The last item here, Findaway? That’s for audiobooks. Audiobook, really. I only have one. This math has made up my mind, however. Authors have reported problems with audiobook accounting for years now, and I believe I’ve sold more than one audiobook in the last year. I’ll be pulling the Savaged by Systemd audiobook from Audible and all other retail channels and making it an exclusive on my web site.

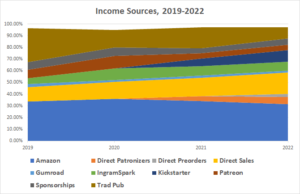

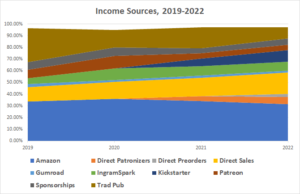

I’ve done these analyses for four years. That’s a little early to start looking for trends, but graphs are easy to create so let’s try it.

Here are the trends over the last four years. For legibility, I have excluded all the sub-1% channels.

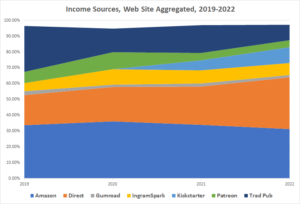

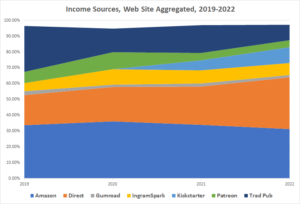

It’s a bit much to call any of these entries “trends.” Kickstarter, direct Patronizers, and direct preorders have squeezed other channels down. But if I aggregate all of the items I offer through my web site, there’s something slightly interesting.

Each year I add options to my web store, like offering bundles of all the tech books and all the novels and collections. I thought nobody would buy either, and that maintaining them would be more work than they were worth. I was wrong. The more different types of stuff I offer for direct sale, the bigger share of my income comes from my web site. Imagine that.

One could argue that Kickstarter and standard Patreon should count as disintermediated. Both offer far better deals than I get from any standard book retailer, and Kickstarter seems great for discovery. Both are external web sites, external dependencies, so they are absolutely not disintermediated.

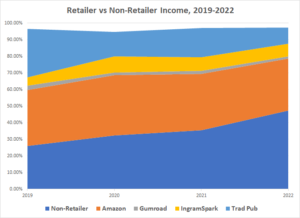

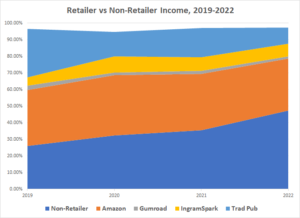

I could count those as “non-retailer” income, however. (My web site is a retailer from where you sit, but my business does not consider it as such.) Let’s see what that does to the graph.

This looks like… a trend?

Non-retailer income is now 47%. Almost half. And consistently increasing. Yes, these sales cannibalize my retailer sales, but Amazon pays me about 70% of cover price and my store pays me about 95% so I can’t complain.

I am stunned. This is incredibly cool. I can’t walk away from retail, but perhaps one day I can somehow deprioritize it.

The truth is, I can take no credit for this trend. My readers looked at their options and said “Yeah, let’s give him our cash directly.” I built it. You came. Thank you.

Part of me still wants to shout “GAZE UPON MY WORKS, YE BEZOS, AND DESPAIR.” Who am I kidding, though? Amazon does not care. I am not worth an hour of a helpdesk tech’s time.

But I care. A lot. Thank you all.

(PS: Someone always asks, “Why don’t you share actual dollar figures?” Declaring my income inevitably leads to people telling me that I can’t possibly be making that much, other people telling me I don’t deserve to make that much, and still other people trying to get “the secret” out of me. It not only steals my time, it increases my annoyance. Not worth it. I will say that I make less than I would in any tech position, but more than most authors.)