I just got asked one too many times, “What’s in this book that’s not in the man pages?” And I’ve snapped.

I’m blogging my answer, so I can point here and save myself from typing the answer again.

I’m best known for writing about BSD technologies, a field where the developers are notoriously detailed in their documentation. If you look at the man pages for any open-source BSD, you’ll see that everything is included. If something is missing, it’s a bug. In addition there are extensive, lovingly-maintained FAQs and community-supported handbooks. How could I possibly add anything to than knowledge?

The short answer is: integration and context.

The man pages almost certainly contain everything you want to know. But man pages are not examples. Man pages do not provide context for the use of that knowledge. The ability to read disparate manuals and assemble that knowledge into a working, cohesive whole is a very specific skill. Programmers, in particular programmers who learn new technologies, have that skill. Many systems administrators develop that skill, after years of practice.

Some people can take a whole pile of man pages, assimilate their contents, integrate that knowledge together, and create a holistic understanding of the field they cover. They can extrapolate from documents into use cases, and reverse-extrapolate from actual uses into configuration. If you are one of these people, I have two things to say to you:

1) You do not need my books.

2) You are smarter than me.

3) By attempting to convince me of things I already know, you are wasting your own time.

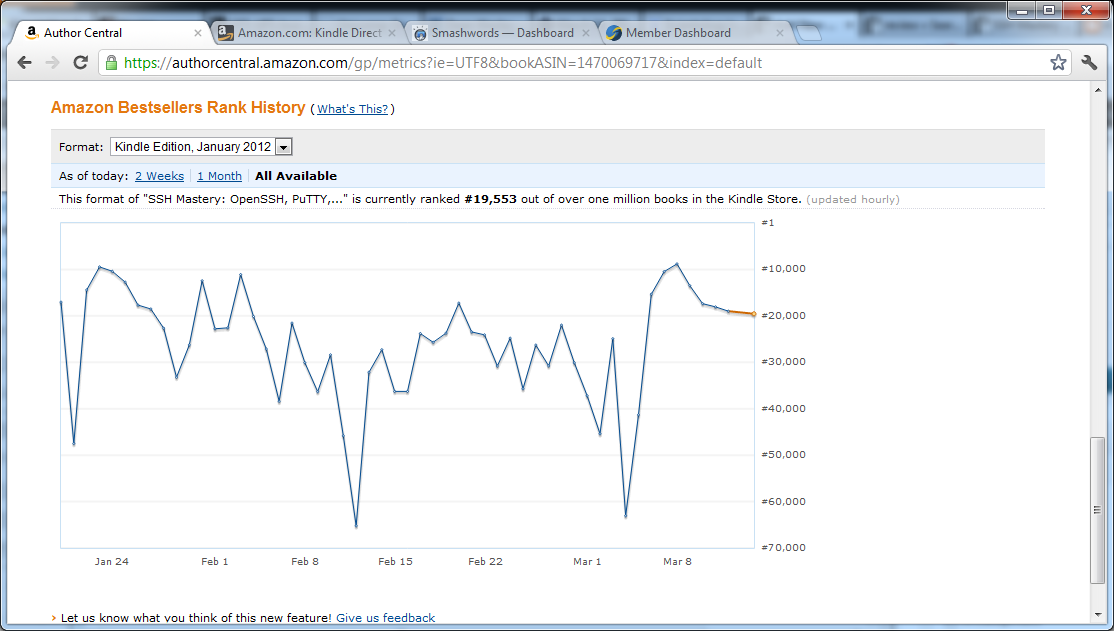

I also concede that many technology books are nothing more than recitals of man pages. Others are nothing more than collections of screenshots, saying “click the Next box” four hundred times. These books are a waste of electrons and wood pulp. I blame them for dragging down the reputation of technology writing. (I also writhe in envy because these books sell far, far better than mine. But that’s a separate issue)

Good technology writing provides context for the information, and guides the reader to create a holistic understanding. Yes, some people can do that purely by reading man pages. Others need help.

Why should I write a book that competes directly with, say, the FreeBSD Handbook or the OpenBSD FAQ? Not everybody learns in the same way. Discussing the same facts in different language, with a different organization, makes the knowledge take a different path through the reader’s mind. The reader’s job is to use new information to make new connections in their brain, and seeing the same information presented very differently can help.

On a personal level, I do my best to make the job of getting that information easy, and present the reader with a whole bunch of ready-made connections.

If you want me to listen to your proclamation of superiority, I have to say: put your money where your mouth is. Donate the list price of one of my books to an open-source project that I write about. If you feel the uncontrollable need to advertise your superiority, write “That Moron Lucas Is Wasting His Time” in the note field. Copy me on the emailed receipt. At that time I will pay attention to you, in direct proportion to the size of the donation. I won’t change what I do, mind you — I probably won’t even answer the email — but I’ll pay attention to you. And I promise you, the recipient project won’t mind.

Update 5/2/2013: With the OpenBSD book coming out, I’m getting more of these. What really amuses me is that people think it’s important that I know the book is not useful.